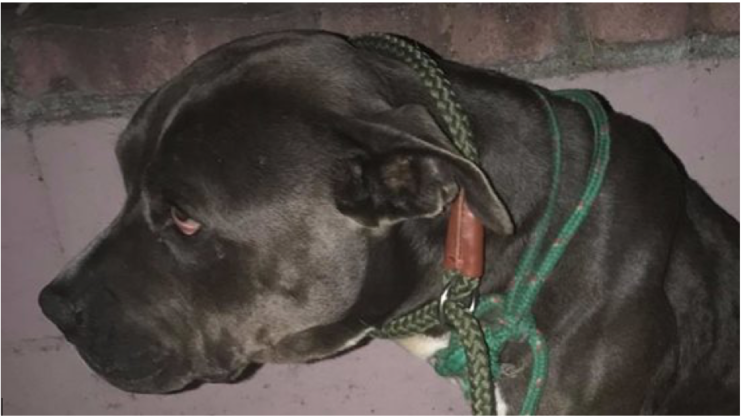

Valerie, a dog adopted from a shelter during a no-fee adoption event, has ended up dead. Although initial information about the case suggested abuse and blunt force trauma (observations made by a veterinary technician), the conclusions of the treating and forensic veterinarians did not find evidence of either. Some well-meaning (and some not-so-well-meaning) people are protesting adoption events such as these as rendering the animals “worthless.” They claim that “without an investment” in an adoption fee, this is the foreseeable result of no-fee adoptions. Is this the lesson to be drawn from poor Valerie’s abuse and killing? In light of the fact that this Saturday, over 700 shelters across the country are participating in a “Clear the Shelters” event that last year saw over 50,000 animals find homes, the answer has immediate and important consequences.

Here’s why I don’t think that it is.

First, setting policy based on extreme examples often makes for bad policy. And as any shelter director and rescuer can attest, a fee doesn’t necessarily guarantee a good home and lack of a fee doesn’t necessarily increase the likelihood of a bad one. In fact, Valerie notwithstanding, there is little evidence that animals adopted from shelters during fee-waived adoption events face increased risk, especially given that the people who are motivated to adopt on a day the shelter is asking for increased public support are demonstrating evidence of caring, not nefarious intent.

According to an article in CatWatch, the journal of the Cornell Feline Health Center:

Some involved with animal welfare are critical of free adoptions of adult cats, believing it devalues the cat in the adopter’s eyes, or it may attract adopters who are unable to fulfill the financial responsibilities of cat ownership: A study in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science examined the attachment of adopters to their cats in relation to payment or fee waiver for adoption. Statistical analysis of the result showed no significant difference in the two groups ‘attachment’ to their adopted cat. The authors conclude ‘implementing a free adult cat adoption program in shelters around the country could dramatically affect the lives of thousands of shelter cats who otherwise either would reside in the shelter for months awaiting adoption or be euthanized. The ultimate goal of shelters is to adopt their animals into loving homes with families who are committed to the success of their pet. The free adult cat adoption program may accomplish these goals, and shelters can feel confident in implementing the program.’

In short, such adoption promotions double and often triple the number of animals who typically get adopted by people who are no less responsible or committed to the animals as those who paid a fee. Moreover, when one shelter I worked with asked for a donation during a no-fee adoption event, the average donation was higher than the standard adoption fee. In addition, adopters have to pay other fees: food and supplies, veterinary care, pet deposits. A “free” adoption is not really free, except for a small portion of the overall cost.

Second, quality and quantity are not, and have never been, mutually exclusive. As one progressive shelter noted:

The best adoption programs are designed to ensure that each animal is placed with a responsible person, one prepared to make a lifelong commitment, and to avoid the kinds of problems that may have caused the animal to be brought to the shelter.

I agree. I have long been a proponent of reasonable adoption screening because I, too, want animals to good homes. In general, I’ve never fully embraced “open adoptions” as some in the No Kill movement do. No fee adoption and adoption screening are not mutually exclusive, as long as that screening is truly reasonable and grounded in logic and evidence. Unfortunately, too many shelters go too far with fixed, arbitrary rules that turn away good homes under the theory that people aren’t trustworthy, that few people are good enough, and that animals are better off dead.

And truth be told, I trust the general public far more than those who run many animal control shelters—those who have become complacent about killing and willfully refuse to implement common-sense life-affirming alternatives. Indeed, the first time many animals experience neglect and abuse and killing is not in the home, but in the “shelter”—the very organization that is supposed to protect them from it. Abuse may not be a foreseeable consequence of no-fee adoptions, but it is of running an agency whose job it is to kill animals. When you are hired to kill animals, when it is right in the job description, too often truly caring people, people who actually love animals, either do not apply to work at these agencies or if they do, they do not last. They realize that their efforts to improve conditions and outcomes is not rewarded, their fellow employees are not being held accountable, neglect isn’t punished, and in fact, too often they are for trying to improve things, and they quit.

And not only does that leave animals at the mercy of people who are willing to work at a very place that commits daily violence on animals (either poisoning them or gassing them to death), they have, in fact, been hired to do exactly that. Can we really be surprised when they don’t clean thoroughly, don’t feed the animals, handle them too roughly, neglect and abuse them, or simply ignore their cries for help? How does shoddy cleaning or rough handling or skipping meals or failing to provide veterinary care compare with putting an animal to death? Because shelter workers understand that they have the power to kill each and every one of these animals, and will in fact kill many (and in some places most) of them, every interaction they have with those animals is influenced by the perception that their lives do not matter, that their lives are cheap and expendable, and that they are destined for the garbage heap.

In other words, getting them out of such places would actually lower the incidents of companion animal abuse. And given that events like Clear the Shelters specifically appeal to municipal and traditional shelters, these are animals who face death. After Saturday, tens of thousands no longer will. And come Monday, hundreds of these pounds will start the week virtually empty, which means the animals who enter it in the coming days and weeks face a dramatically reduced risk of being killed.

I am not downplaying what happened to Valerie and any abuse is horrific. But what happened to Valerie was not the norm. In fact, she was adopted without any real screening. Policies are easily put in place to prevent this. But shelter abuse and killing are not an aberration. Indeed, shelter animals already face formidable obstacles to getting out alive: customer service is often poor, a shelter’s location may be remote, adoption hours may be limited, policies may limit the number of days they are held, they can get sick in a shelter, and shelter directors often reject common-sense alternatives to killing. Two million dogs and cats are poisoned to death, given a heart attack by heartsticking, or gassed to death in pounds because of these obstacles. Since the animals already face enormous problems, when kind-hearted people come to help, shelter bureaucrats shouldn’t start out with a presumption that they can’t be trusted.

In fact, most of the evidence suggests that the public can be. For those of us in the trenches of running a shelter, shelter reform, rescue, or advocacy, it is too easy to become myopic, to believe that few people care about cats, dogs, and other companion animals and that people going out of their way to help animals in need is the province of the few. Working in animal rescue, it is too easy to believe the world is a cruel, dark place filled with cruel, dark people. It isn’t.

The vast majority of Americans say we have a moral duty to protect animals and should have strong laws to do so. Three out of four Americans believe it should be illegal for shelters to kill healthy and treatable animals. The senior animal is the fast growing segment of the pet population because over 80% see their animals as “surrogate children” and keep them for life. Indeed, specialization and advancements in the field of veterinary medicine have been driven by a population of Americans willing to spend and do whatever it takes to save the lives of the animals they love. In fact, spending on our animal companions is the seventh largest sector of the retail economy, growing at a rate 50% higher than the overall economy, showing steady annual increases even in the face of economic uncertainty, and will top $70 billion this year. Only a small fraction of the 175 million animals in people’s homes will ever see the inside of a shelter and of those, only four percent are seized because of cruelty and neglect. These statistics refute the notion that most companion animals encounter cruelty from human strangers, rather than kindness or a helping hand. While abuse of animals does occur, it is not the norm. In fact, it is considered aberrant behavior which should be punished.

We are a nation of animal lovers, and we should be treated with gratitude, not suspicion. More importantly, the animals facing death deserve the second chance that many well intentioned Americans are eager to give them, but in too many cases, are senselessly prevented from doing so with arbitrary rules that falsely assume that everyone will treat animals the way Valerie was treated and that they can prevent this by restricting adoptions. But restricting adoptions only means more animals will be injected with poison before their lifeless bodies are put in garbage bags and sent to rot in landfills. And that is not the lesson to draw—or the outcome to seek—from what happened to Valerie.

RIP little one.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.