A history of the No Kill movement through political cartoons

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. And when those pictures are political cartoons, they speak in volumes. Political cartoons endure precisely because they are razor sharp in their attention, telling us all we need to know for or against some proposition. From the earliest days of our Republic, the political cartoon has served to dramatize current events and put opposing views into stark contrast. And the No Kill movement has been no exception. Here are some cartoons which define key events in the history of the movement, and help to illuminate the fight for a No Kill nation. [Click on each picture for a larger view.]

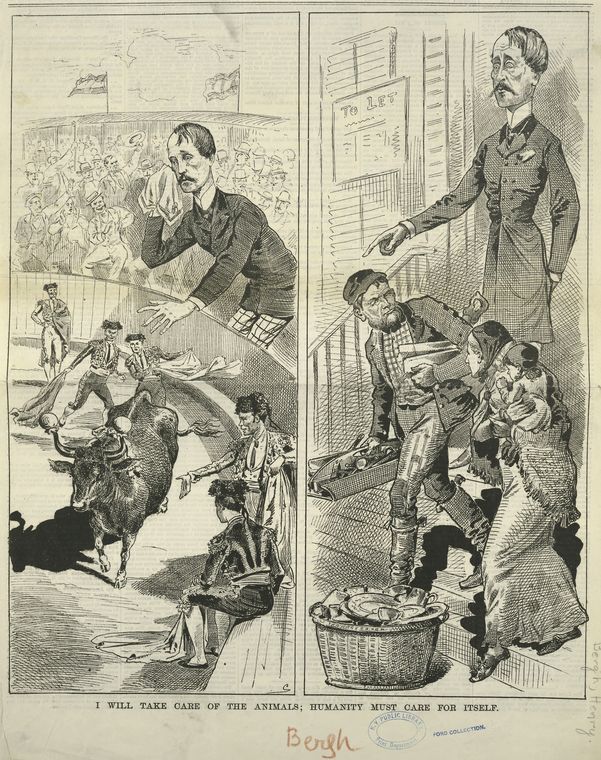

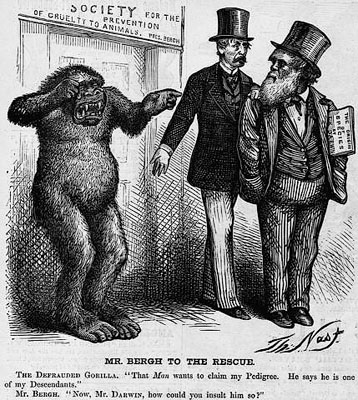

Trivializing Compassion

Henry Bergh was the 19th Century animal advocate who launched the humane movement in North America. He gave the first speech on animal protection in the U.S., incorporated the nation’s first humane society (the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals), and succeeded in getting the New York State legislature to pass the nation’s first anti-cruelty law.

After he succeeded in getting an anti-cruelty law, he put a copy in his pocket, and took to the streets that very night—and every single night thereafter for the remainder of his life—to patrol the streets of his native New York City looking for animals in need of protection. The annals of the ASPCA describe the first such encounter:

The driver of a cart laden with coal is whipping his horse. Passersby on the New York City street stop to gawk not so much at the weak, emaciated equine, but at the tall man, elegant in top hat and spats, who is explaining to the driver that it is now against the law to beat one’s animal.

Among many other achievements, he even invented the clay pigeon to put an end to cruel pigeon shoots. If he were alive today, there is no doubt that Bergh would be the nation’s most vociferous No Kill advocate and a fierce critic of the ASPCA he founded.

Sadly, the political cartoons of Bergh’s day often mocked him. Here, two cartoons depicting Henry Bergh try to assassinate his character by claiming he cares about animals, but not people. In the cartoon above, Bergh is weeping at a bull fight but telling the poor of New York City to get off his property. In the cartoon below, Bergh is chastising Charles Darwin for insulting the crying gorilla by suggesting the gorilla is related to humans.

Of course, Bergh’s compassion was not limited to animals: Bergh also rescued abused children. In 1874, less than a decade after incorporating the ASPCA, he formed the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, the first child protection organization in the nation, effectively launching the children’s rights movement in the United States.

The Death Camps

In contrast to the Pollyanna pieces done by comics such as Patrick McDonnell about shelters (Mutts), this piece actually captured the typical American animal control shelter. Animal control, supported historically by groups like the Humane Society of the United States, consider being a lost, stray or feral cat a death sentence. Animal Control officers are often empowered to round them up and kill them. And these organizations promote and embrace laws which give animal control officers even more power. In California, a proposed law in 1994 would have empowered officers to kill cats immediately upon capture on the street if they did not have proof of a rabies vaccination—which would have resulted in mass slaughter. This 1995 cartoon captured that reality.

While McDonnell’s work is guided by an obvious compassion for homeless animals and he donates proceeds from his book signings specifically to No Kill shelters, his depiction of shelter directors and staff as hard working, compassionate, lifesaving-driven animal lovers crumbles in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

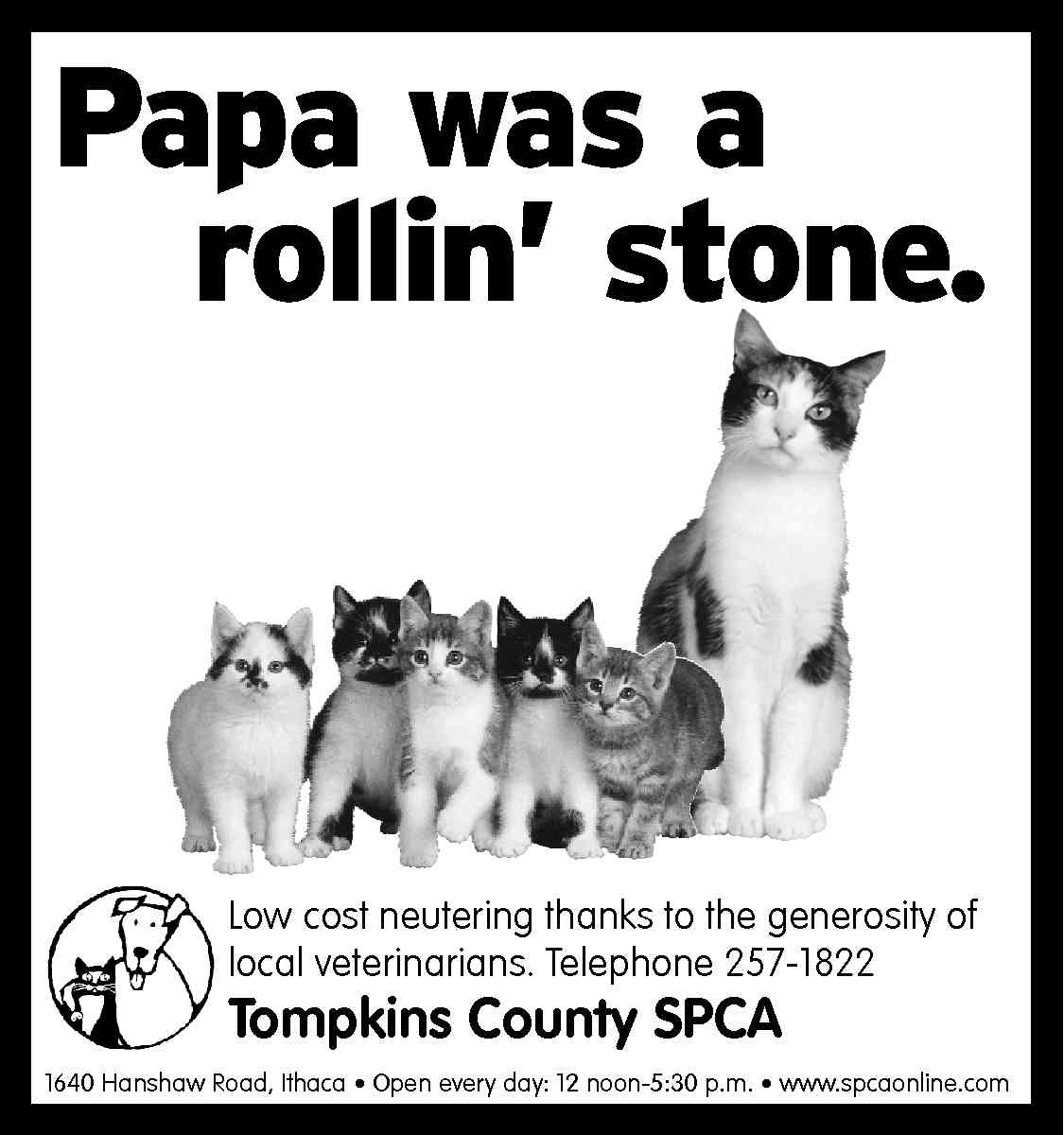

Approaches to Spay/Neuter

Rather than accuse people of being irresponsible, rather than rant about “pet overpopulation” and the “need” to kill, all of it of dubious value and truth, and rather than seek mandatory spay/neuter laws which empower animal control to impound and kill more animals, this piece summarized the shelter’s desire in five humorous words. Though not a political cartoon, per se, the Tompkins County ad of my tenure was as biting and dramatic as one (copy of the original from the San Francisco SPCA). Tompkins County became the first No Kill community in U.S. history on the back of strong community support, something “pet overpopulation” “mandatory spay/neuter” and “irresponsible” ranters have never, ever been able to achieve.

The Last Gasp of the Dinosaurs

In 2004, as the No Kill movement gained momentum following Tompkins County, NY’s success and with the founding of the No Kill Advocacy Center, the architects of the status quo met in Asilomar, California to take back their hegemony over the sheltering discourse. They identified the terms “No Kill” and “killing” as hurtful and divisive and demanded that they ceased being used. They argued that the decision to save lives through TNR, offsite adoptions, and other needed programs should not be forced on shelters but left to their own determination. They also argued that killing was not their fault. Despite this, they claimed they were committed to saving healthy and treatable animals, narrowly defined to exclude whole categories of animals including feral cats. Groups like HSUS pledged to enforce the “Asilomar Accords” and traveled the country telling groups they could not call themselves “No Kill” or use the term “killing” for animals killed in shelters. By the end of the decade, only two communities had embraced the Accords, however, and though it lives on for record keeping purposes among some groups, the Asilomar Accords were challenged by the U.S. No Kill Declaration, and found them essentially, “Dead on Arrival.”

This cartoon from the No Kill Advocacy Center shows the dinosaurs trying to cling to the status quo, as they are about to get wiped out of existence by a meteor which represents the No Kill movement. Pictured are some of the Asilomar Accords’ signatories: HSUS, the National Animal Control Association, Denver Dumb Friends League, and Ft. Wayne Animal Control, shelters and organizations with a long, dubious history of killing and/or fighting the No Kill movement’s lifesaving innovations.

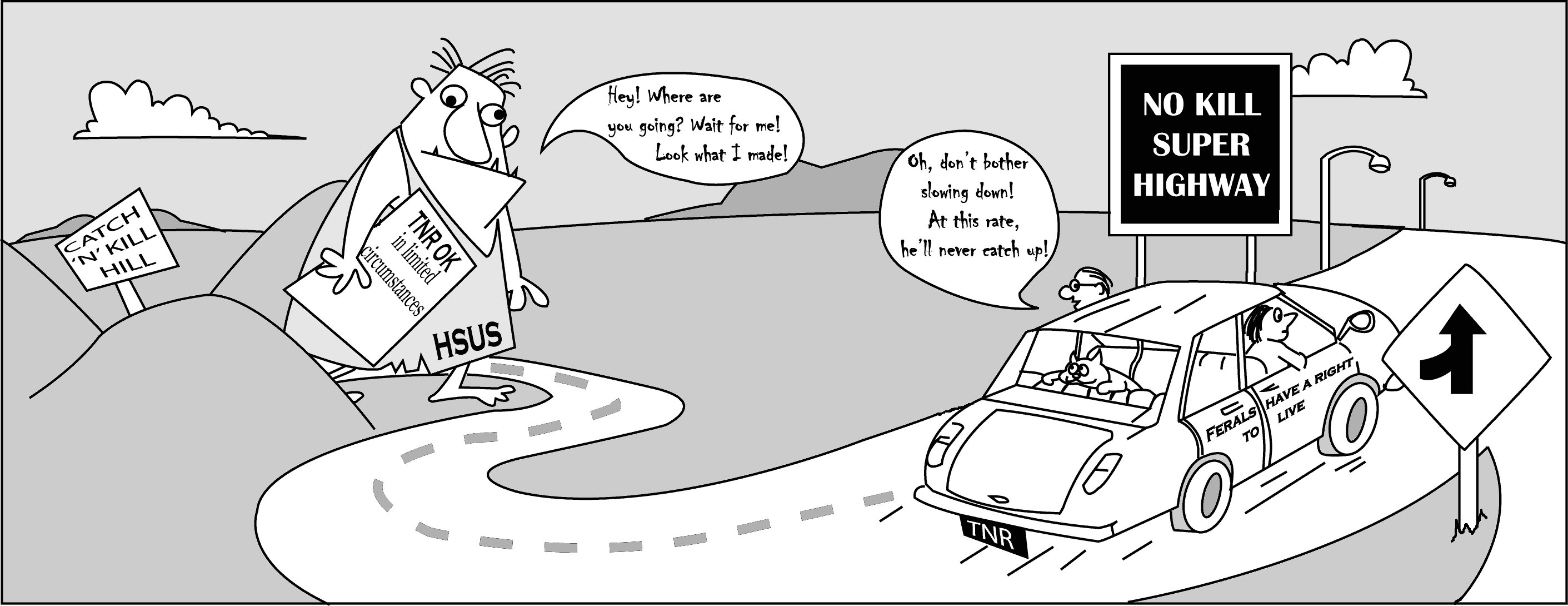

TNR Takes the Movement by Storm

The Lumbering Giant says TNR is O.K. except when it is not O.K.

The Lumbering Giant says TNR is O.K. except when it is not O.K.

In 2006, after decades of calling Trap-Neuter-Release (TNR) programs for cats “inhumane,” “abhorrent,” and “subsidized abandonment,” after asking a prosecutor to arrest and jail feral cat caretakers for violation of state cruelty laws against abandonment, and after calling mass killing of feral cats in pounds and shelters “the only practical and humane solution,” the Humane Society of the United States indicated it was updating its feral cat position to reflect the emerging consensus of the animal control community, a community with a history of mass slaughter. They had no choice.

At the end of the 1990s, only a small handful of shelters embraced TNR as an alternative to killing of feral cats. But cat lovers across the country rallied on behalf of the cats, and with communities like San Francisco using TNR to reduce the feral cat death rate by over 80%, with Tompkins County becoming the first open admission shelter to zero out deaths of feral cats through TNR, and with the advocacy of TNR on a local, regional, and national scale by groups across the country, any question of the legitimacy and efficacy of TNR was erased. TNR took the movement by storm. And HSUS was forced to follow. Their March 2006 statement said “TNR was ok” but only in very limited circumstances, essentially writing in several exceptions that swallowed the rule including:

- TNR efforts must be limited if someone says that feral cats are a threat to wildlife;

- Feral cat caretakers must respect the “limitations” of other groups in the area, including those who may not share their views about feral cats; and,

- Killing of feral cats can continue for an undefined “interim period.”

Taken to their logical conclusion, these “limitations” were so severe they effectively nullified any ostensible support for TNR in the 2006 statement. There is no feral cat colony anywhere in the United States, for example, where some wildlife is not also present. HSUS was asking feral cat advocates to make the decision “about whether to maintain a particular colony” after a determination of “the potential negative impact on local wildlife.” To make this determination, HSUS further asked feral cat caretakers to “respect” the views of all interested parties—which potentially includes animal control and Invasion Biology proponents who do not support TNR.

The unspoken converse to deciding whether to maintain a particular colony is deciding whether to eradicate it. That is the choice presented, providing a powerful tool to the enemies of TNR. Essentially, it means that feral cats can be excluded from locations whenever someone says wildlife is impacted, which could potentially happen everywhere. In fact, these are exactly the types of claims being made all over the United States, and while HSUS says it no longer favors eradication, what is the alternative to TNR, other than doing nothing?

If, as HSUS claims, cats kill wildlife, are a rabies threat and an “invasive non-native species,” and cause neighborhood strife, does this mean that TNR is acceptable so long as the cats are kept away from neighborhoods, people, birds and other wildlife? Because these conditions exist nowhere, it would appear to mean that TNR is acceptable so long as the cats are not allowed outdoors—a logical absurdity.

In the No Kill Advocacy Center’s cartoon above, the lumbering, sleeping giant, HSUS, wants to tell the feral cat community all of this, but TNR proponents have moved on with the firm and unequivocal position that feral cats have a right to live, regardless of what HSUS, Audubon Society and its acolytes, and regressive animal control shelters have to say about it. In a short period of time, HSUS was forced to abandon the statement in favor of more open acceptance of TNR. But by then, was anyone listening?

Angels of Death

The realization that People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), a group which advocates against killing animals for food, sport, and otherwise, nonetheless opposes No Kill, champions mass slaughter of companion animals in shelters, calls for the ban—and therefore systematic extermination—of all dogs someone says look like “Pit Bulls,” says feral cats are better dead than fed, and kills roughly 2,000 animals every year they seek out, shocks and outrages the true animal lover.

While No Kill was coming into its own over the last decade and shelters across the country were saving better than 90% of all animals on a fraction of PETA’s budget, PETA continued to move sharply in the other direction. PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk spent the decade not only attacking No Kill, but actively seeking out animals to kill (roughly 90% of them). The total body count from 2000 – 2008 (2009 figures not yet available): 19,326. Once the 2009 figures are released, the number will skyrocket past 20,000: that’s roughly 2,000 animals a year that PETA has killed every year for the last decade; or over five animals killed by PETA every single day of the last ten years.

In this No Kill Advocacy Center cartoon above, a dog dresses like a chicken in hopes of getting PETA to care about him, too. Unfortunately, the previous cartoon turned out to be wrong. PETA also kills other animals, including chickens, as well, which it does at its Norfolk, VA facility. The cartoon below turned out to be more accurate, as the chicken in the shelter fears for his life as much as the dogs and cats do.

In 2006, PETA staff was arrested for killing animals they promised to find homes for, and then discarding their bodies into local supermarket dumpsters. Although they were acquitted of animal cruelty and other charges since it is not illegal for a “certified euthanasia technician” to kill animals if connected to an organization that has registered itself as a shelter, testimony during the court case showed that PETA went to shelters and private veterinarians to get animals, telling some they would find them homes, and killed the animals, often within minutes of departing in the back of a van. One veterinarian who gave PETA a healthy mother cat and her kittens testified that the animals were never at risk for being killed in his practice; he was simply looking for homes for them. He gave them to PETA because he thought they would have no trouble finding them homes. PETA staff killed them within minutes. Their bodies were found in a dumpster a short time thereafter.

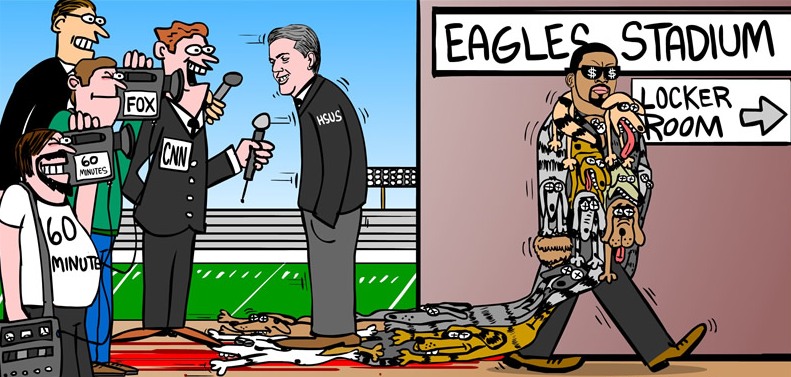

Riding on Michael Vick’s Bloodstained Coattails

Despite a series of pro-killing scandals that have marked his tenure, Wayne Pacelle, the beleaguered and uncaring CEO of the Humane Society of the United States, shocked even his supporters by embracing Michael Vick, the most notorious dog abuser of our time. Vick took pleasure in seeing dogs tear each other apart. He took pleasure in beating dogs to death. He took pleasure in hanging dogs by the neck. He took pleasure in electrocuting dogs. He took pleasure in shooting dogs. And he took pleasure in drowning dogs.

After being convicted on federal dog fighting related charges, Vick was banned from the NFL. But Vick sought to escape permanent punishment by doing the time-honored tradition of the scoundrel: hire a P.R. team to reform his image, issue a “mea culpa,” do some carefully orchestrated appearances with kids, and then get his old life back. Wayne Pacelle was eager to assist him to do that. With the help of Pacelle, Vick gets his life back, becoming a millionaire once more, while the dogs he killed are, well, still dead. Vick follows up by saying he wants dogs again: will HSUS help him with that also?

While Pacelle, through HSUS, testified that the dogs Vick abused should not be given a second chance and should all be killed, Pacelle said that their abuser should be. Vick became a spokesman for HSUS. Or was it the other way around? In the nokillblog.com’s cartoon, Pacelle rides Vick’s blood-stained coattails to his favorite destination—the front pages of the New York Times, 60 minutes, and other media.

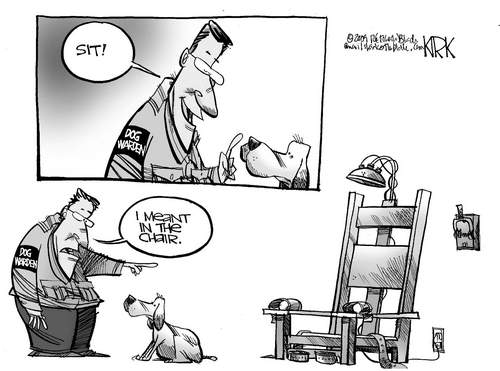

Convenience Killing

As occurs all over the country, Tom Skeldon, the Lucas County, Ohio dog warden, killed animals, despite readily available lifesaving alternatives. Indeed, he killed dogs and puppies even when rescue groups and humane societies offered to save them. In this Toledo Blade cartoon, Skeldon is telling a dog to sit, which the dog does, demonstrating that he is a kind, friendly, and obedient dog, which should please the warden. It doesn’t. Skeldon wants the dog to sit in the electric chair, so he can be put to death. What made this cartoon so dramatic is that it resonated so strongly with the experience many rescuers have of their own dog wardens and pound directors. Skeldon may have been less polished than others, but he was hardly unique. Indeed, this comic could have been published in virtually any newspaper—Houston (TX), King County (WA), Los Angeles (CA), and hundreds of other cities—and it would have had the same meaningful impact. Thankfully, Skeldon was forced out, but others like him remain entrenched in shelters all across the country.

The Meaning of Oreo’s Law

In November of last year, the ASPCA killed an abused dog named Oreo, despite an offer by a No Kill shelter to save her life. In response, the New York State Legislature is now considering a law that would make it illegal for any shelter or pound to kill an animal if a legitimate rescue group is willing to save the animal’s life. But the ASPCA wants to kill the proposed law, the way it killed Oreo, for which the new law is named.

While the animal loving people of New York State flood the legislature with calls of support, while the most progressive voices in the companion animal movement have embraced and endorsed Oreo’s Law, and while rescuers anxiously await legislation that will empower them to save the lives of thousands of animals every year, the leader of the nation’s wealthiest SPCA stands alone in defiant opposition, thumbing his nose at them all.

This cartoon from YESonOreosLaw.com shows a shelter killing dogs and cats that rescue groups are there to save. Oreo’s Law would give them that power but Ed Sayres, the President of the ASPCA, is trampling Oreo’s Law and holding them back, which will cost animals their lives.

Regardless of whether animals and animal lovers win by passing Oreo’s Law in this session of the legislature, Ed Sayres and the hacks he recruits to oppose it (or to remain deafeningly silent) will lose. Indeed, Sayres is already paying a price. While he assured his staff that the anger over Oreo’s killing would subside in a few days, it still hasn’t three months later and the fight for Oreo’s Law is intensifying calls for his ouster. At the same time, the fight over Oreo’s Law has clearly shown rescuers and animal lovers which groups they can count on to champion the animals and which groups they can’t.

And this much is clear: if animal rescuers win, so do the animals. And if Oreo’s Law passes, animal rescuers will win big across the country. As one reformer stated, “Where New York goes, so goes the nation.” Indeed, the next phase of the quest for a No Kill nation will not center on adoption ads or social media—these will achieve widespread acceptance—the FIGHT will be in the halls of Albany, NY, Sacramento, CA, Austin, TX, and other state capitals. Because how do you achieve and sustain a No Kill nation if shelter directors keep the discretion they currently have to avoid doing what is in the best interests of animals and kill them needlessly? You can’t. Oreo’s Law is just the first wave of a national effort to shift the balance of power back to the animals—and their rescuers.