Two cats stuck on a power pole in two different cities highlight the good and ugly side of animal shelters.

How can we help?

It should be the underlying philosophy of every humane society and SPCA. The answer to that question manifests itself in myriad ways: A staff member staying late to process an adoption application. An officer knocking on the doors of a neighborhood to return a lost dog, rather than impounding him into the shelter. Helping to rescue a stranded kitten.

Day in and day out, the question “How can we help?” has big dividends: in Reno, Nevada, it has paid off big in terms of adoptions, reclaim rates, awards, donations, and for the animals, the numbers of lives saved. Today, Reno has one of the highest lifesaving rates in the nation. The approach isn’t novel. It is, in fact, what our movement was founded to do.

Henry Bergh, the 19th Century founder of our movement, was once flagged down by a number of people who heard a cat crying at a construction site. Bergh determined that the cat had been entombed inside a wall and ordered the construction crew to open the wall. The foreman balked, saying doing so would cost money and suggesting that the cat be left inside. Bergh took a sledgehammer to the wall himself, freeing the cat to the delight of passersby. Far fetched? Not really.

Houston, Texas, for example, has long been criticized by animal lovers in that community for deplorable conditions in its shelters and high rates of killing. Historically, those job seekers who scored the lowest on city aptitude tests were placed in animal control by design, and it showed. What did it matter if that meant animals would be neglected and tens of thousands would be needlessly killed? Not their problem. And don’t even think about calling local groups and agencies for help—even when the life of an animal hangs in the balance, as a frantic person learned when she called to get help after her cat got stuck on a power pole.

According to KHOU News in Houston,

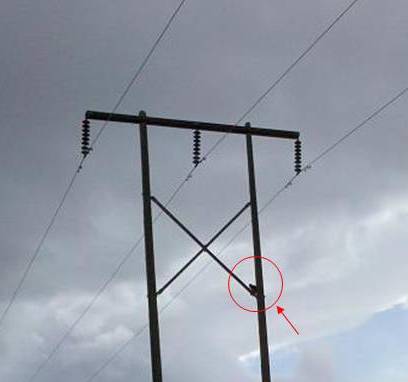

The owner of a kitten that died after getting stuck up on a power pole wants to know why no one would help her save her pet. Lauren Kutac’s 8-month-old kitten spent 47 hours on the pole located in the backyard of her home in southwest Houston before she was electrocuted in the middle of the night.

“You just heard, ‘pow,’ and all the electricity went out,” said Lauren Kutac. “I scaled my back fence and she was, she was just fried.” The cat lover said she called several agencies including the Houston Fire Department, the SPCA, the Houston Police Department, and [the local electric company] while she was sitting on the pole. They all declined her request for help. “Not one person could help me,” she said.

Is it any wonder that Houston, Texas, has one of the highest rates of killing not just in Texas, but anywhere?

Ironically, the same thing happened in Reno: A frightened cat got stuck on a power pole. But instead of saying it wasn’t their problem, as the local SPCA, city agencies, and even the power company told the kitten’s caretaker in Houston, they asked the question “How can we help?” And the results show it.

According to the Nevada Humane Society,

What goes up must come down—whether it wants to or not. Such was the case with a cat who climbed near the top of a 40-foot-high power tower in Washoe Valley on Friday, March 5. The five-year-old male tuxedo cat became frightened and couldn’t climb back down the pole. Washoe County Regional Animal Services Officer Cindy Doak came to the rescue and through the use of a boom truck, the kitty was soon lowered to safety.

Sparky, affectionately named by his rescuer Officer Doak, is now under the care of Nevada Humane Society and after being neutered, vaccinated and microchipped, is ready for adoption.

“Sparky is a sweet, cuddly and affectionate kitty, in addition to being quite handsome,” explained Kiersten Phillips, Lead Cat Caregiver for Nevada Humane Society. “He shows no negative signs from being trapped at the top of the pole and is eager for a loving home.”

Such a different outcome in Reno provides a stark contrast to the dark underbelly of regressive and draconian animal shelters in this country. A community’s animal shelters are part of the service industry, and leadership and staff should be determined to faithfully serve the community which pays their salaries through philanthropic and tax dollars. They are there to help the animals, and to help people with animal related issues. And the most successful shelters do that really well: from proactive efforts to help people reclaim lost pets, to an animal help desk designed to resolve animal related conflicts, to public access adoption hours, to low-cost spay/neuter, holiday events so families can do good deeds together, to making it easy for people to do the right thing, the most successful shelters in terms of lifesaving are also the most service oriented.

But you wouldn’t know that if you called most shelters for help. You’d be lucky if they answered the phone. And if they did, you’re likely to be treated rudely. A trip to the shelter would be a tour de force of poor customer service, dirty facilities, and a tidal wave of bureaucratic indifference. You are there to adopt? It doesn’t matter to them if you do or you don’t, it’s not their problem. You’d like to volunteer. Again, not their problem. You are part of a rescue group and you’d like to pull animals off of death row, but you expect them to notify you before killing an animal? “Unreasonable” they say. And, don’t even think about offering to bottle feed kittens around the clock at no cost to them in order to save lives. Meanwhile, all the animals you’d be trying to help by this will be put to death. And the staff who does so will blame you for the killing. You are, after all, part of the “irresponsible public.”

As a woman learned when she tried to save the life of a scared cat at her local shelter:

I tried to adopt from my local shelter, but they weren’t open on the weekend, it was almost impossible to reach them on the telephone and when I did, I was treated rudely. Nonetheless, I raced down there one day after work, and the place was so dirty. It made me cry to look into the faces of all those animals I knew would be killed. But I found this scared, skinny cat hiding in the back of his cage and I filled out an application. I was turned down because I didn’t turn in the paperwork on time, which meant a half hour before closing, but I couldn’t get there from work in time to do that. I tried to leave work early the next day, but I called and found out they had already killed the poor cat. I will never go back.

If 2009 symbolized anything, it showed the dual and disparate nature of animal sheltering in the U.S. On the one hand, anti-No Kill organizations like the ASPCA insisted on their right to kill animals even in the face of a rescue alternative by putting dogs to death who had lifesaving opportunities. They then used their war chest, which includes their Sarah McLachlan “Arms of an Angel” commercial (that generates roughly $30 million per year for the ASPCA), to vilify rescue groups and fight legislation that would save the lives of these animals.

Recent scandals included shelters who starved animals to death, who poured bleach on them while staff laughed, who specifically killed animals rescue groups were on their way to save, who allowed animals to go without medication so that they died in their cages, and who beat puppies to death. These scandals and other not only showed that rampant killing in the face of readily available lifesaving alternatives is the norm, but that the killing is too often preceded by neglect and abuse, some of it of the most horrific kind.

But 2009 also saw the increasing success of other communities who asked the question: “How can we help?” and then faithfully saw to it that they followed through. New communities that did so hit 90 percent level save rates, including San Francisco Bay Area cities Berkeley, Piedmont, and Emeryville, California, Reno, Nevada, Shelby County, Kentucky, as well as communities in Kansas, Indiana, and others. And those communities which have been historically successful, repeated those successes, including Tompkins County, New York, which has now saved at least 92% for each of the last seven years, Charlottesville, Virginia, and still others.

How can we help? It is music to the animal lover’s ears.