If you could sit down and have a drink with any five people in history, who would be on your list? For everyone at the Winograd house, the top five always includes Henry Bergh.

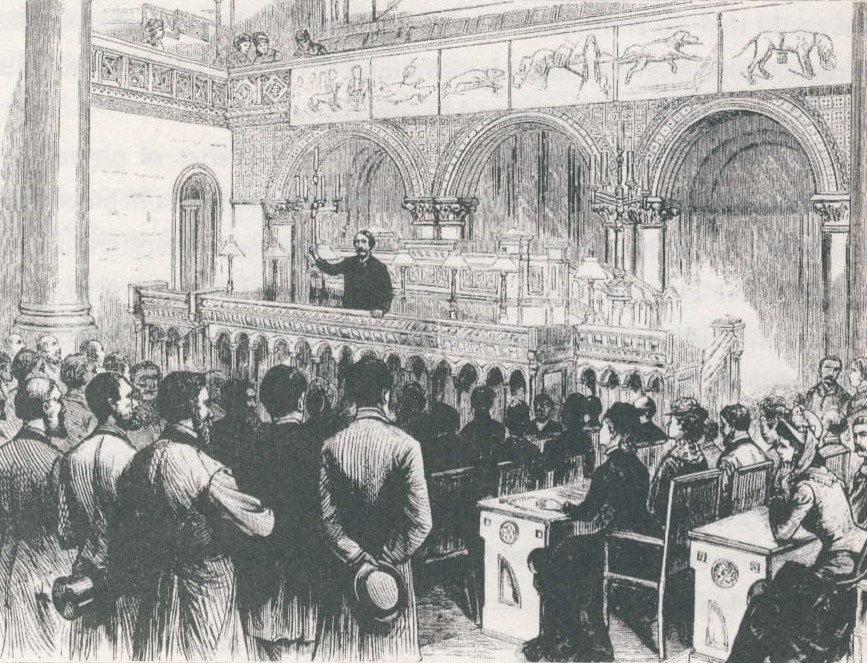

To those who have seen Redemption, my documentary film about the No Kill revolution in America or read the book on which it is based, Henry Bergh needs no introduction. To those who haven’t, Henry Bergh was a 19th Century animal advocate who incorporated the nation’s first SPCA and helped launch the humane movement in North America.

The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote of him,

Among the noblest of the land; Though he may count himself the least; That man I honor and revere; Who, without favor, without fear; In the great city dares to stand; The friend of every friendless beast.

And he was, as A Traitor to his Species, a new biography of Bergh and the animal rights movement he birthed, makes clear. After he succeeded in getting New York State to pass an anti-cruelty law, he put a copy in his pocket, and took to the streets that very night — and every single night thereafter for the remainder of his life — to help animals and punish violators, from cruel dog catchers to horse abusers. The annals of the ASPCA describe the first such encounter,

The driver of a cart laden with coal is whipping his horse. Passersby on the New York City street stop to gawk not so much at the weak, emaciated equine, but at the tall man, elegant in top hat and spats, who is explaining to the driver that it is now against the law to beat one’s animal. Thus, America first encounters ‘The Great Meddler.’

And meddle he did. “Day after day,” he wrote,

I am in slaughterhouses; or lying in wait at midnight with a squad of police near some dog pit; through the filthy markets and about the rotten docks; out into the crowded and dangerous streets; lifting a fallen horse to his feet, or perhaps sending the driver before a magistrate, penetrating dark and unwholesome buildings where I inspect collars and saddles for raw flesh; then lecturing in public schools to children, and again to adult Societies. Thus my whole life is spent.

Bergh fought for horses, dogs, cats, animals raised and killed for food, and more. Every time he was told he should stick to dogs or horses and was going too far, as when he attempted to ban the shooting of pigeons, the killing of rats, or to get a law passed banning vivisection (laboratory and medical school experiments on animals), Bergh was undeterred,

Almighty God: entertains no discriminating partiality for any of His creatures but His affection is extended to all alike:

The insect in the plant, the moth which spends its brief hours of existence in hovering about the candle’s flame, nay, the life which inhabits a drop of water, is as much an object of his special Providence as the mightiest monarch on his throne.

Although he is not a very well known figure, we and the animals owe him a great deal. Every humane society that stands up for animals; every animal protection group that gives voice to the voiceless; and the millions of animals who have been saved thanks to the efforts of activists and advocates, are a living legacy to his life. Bergh was one of the first Americans to begin weaving the ideals of animal protection into our jurisprudence, the American psyche, and the fabric of American life.

While some of the conclusions drawn about Bergh in this newest biography are wrong and some quotations are taken out of context (for example, practicality in terms of affecting change is assumed to be depth of belief), A Traitor to his Species is a great introduction to Bergh, his accomplishments, and his legacy. (I also disagree with the author’s conclusion that Bergh’s focus on individual rights was a mistake because he was blind to species extinction. To the contrary, had the environmental movement embraced Bergh’s individual rights approach, it would not have become corrupted by nativism, nor would it have embraced an approach that is the polar opposite of intended purpose — using poisons, guns, and traps to kill the very plants and animals it should be protecting.)

Admittedly, like all men, Bergh had his blindspots, but there is no denying that Bergh was also well ahead of his time and a true visionary when it came to animals. When you have finished it, it will not only make you want to raise a glass to him, but like the Winograds, make you wish you could have a glass with him, too.

A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement, by University of Tennessee professor Ernest Freeberg, is available on Amazon and wherever books are sold.

Redemption, my documentary about Bergh, is free on YouTube.

And the book on which the documentary is based is available on Amazon.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.