By Nathan & Jennifer Winograd

Today, an animal entering an average American animal shelter has a 50 percent chance of being killed, and in some communities it is as high as 99 percent, with shelters blaming a lack of available homes as the cause of death. But is pet overpopulation real? And are shelters doing all they can to save lives? If you believe the Humane Society of the United States, the American Humane Association, the ASPCA and PETA the answer to both those questions is “yes,” even though that answer flies in the face of the data and experience. It is simply “received” rather than substantiated wisdom. To adherents of the “we have no choice but to kill because of pet overpopulation” school, pet overpopulation is real because animals are being killed, a logical fallacy based on backwards reasoning and circular illogic. In other words, data, analysis and experience—in short, evidence—have no place. Neither do ethics.

In truth, and at the heart of the No Kill philosophy, is the understanding that the reasons we have historically been given for why animals are being killed in shelters—there are too many for too few homes available, and that the American public is uncaring and irresponsible—have been proven wrong in the face of data and communities that are achieving No Kill level save rates not by changing the habits of the people within a community, but by changing the culture, policies and procedures of the shelter itself. In other words, we know pet overpopulation is a myth because both the statistics and the experience of progressive shelters prove it is.

Some eight million animals enter shelters every year and while apologists for shelter killing will tell you that we cannot adopt our way out of eight million animals, the truth is that we can. That is good news. But the even better news is that adopting out eight million animals isn’t what we have to do. The actual number of animals needing homes is much less. Some animals entering shelters need adoption, but others do not. Some animals, like free-living, unsocialized (“feral”) cats, need neuter and release. Others will be—and many more can be with greater effort—reclaimed by their families. Others are irremediably suffering or hopelessly ill. And many more can be kept out of the shelter through a comprehensive pet retention effort. While about four million dogs and cats will be killed in pounds and shelters this year, roughly three million will be killed for lack of a new home. Can we find homes for three million animals? Yes.

Using the most successful adoption communities as a benchmark and adjusting for population, U.S. shelters combined have the potential to adopt almost nine million animals a year. That is almost three times the number being killed for lack of a home. In fact, it is more than total impounds; and of those, almost half do not need a new home. But the news gets even better because the number of people looking to get an animal is so much larger than the shelter “supply.”

There are over 23 million people who are going to get an animal next year. Some are already committed to adopting from a shelter. Some are already committed to getting one from a breeder or other commercial source. But 17 million have not decided where that animal will come from and research shows they can be influenced to adopt from a shelter. That’s 17 million people vying for roughly three million animals. So even if 80% of those people got their animal from somewhere other than a shelter (or were denied the ability to adopt from a shelter for whatever reason), we could still zero out the killing. And many communities are proving it.

A before and after snapshot of the nearly 100 communities which now have save rates between 90% and 99% show that their shelters achieved that rate of lifesaving by changing the way they operated. Contrary to what conventional wisdom has prescribed for decades, they did not change the public. That’s because animals are not and have never been killed in shelters because of the choices made by the public. Instead, they are being killed because of the choices made by the people overseeing our shelters.

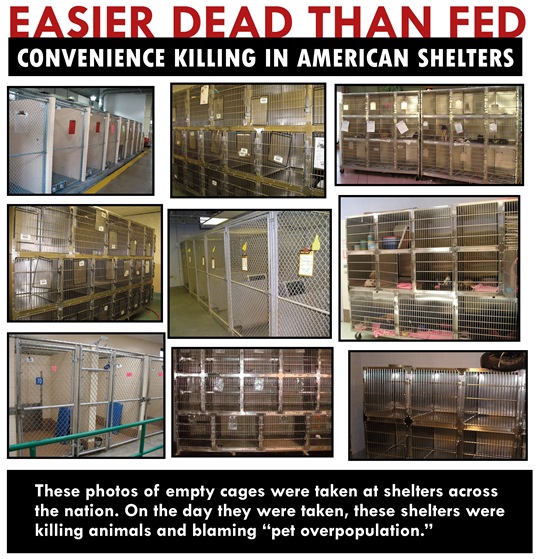

In traditional U.S. animal shelters and despite decades of public assurances to the contrary by our nation’s shelter directors and animal protection organizations, animals are killed primarily out of habit and convenience. Visit an animal shelter run in line with traditional sheltering protocols, and this will become evident in a variety of ways. You will see animals killed rather than placed in available cages so staff doesn’t have to clean those cages or feed the animals inside them. Not only do sheltering policies promoted by large animal protection groups such as HSUS recommend keeping cages and kennels empty, but I have visited shelter after shelter where animals were being killed allegedly “for space” while at the same time those shelters had plenty of empty cages, sometimes entire rooms of them. On a day I visited the Carson shelter of the Los Angeles Department of Animal Care & Control, a shelter where roughly eight out of 10 cats are put to death, 80% of the cages were intentionally kept empty. When I visited Shreveport, Louisiana’s shelter, only one cat was available for adoption despite a 92% death rate for cats. In Eugene, Oregon, at a time it was killing 72% of cats and claiming to do so for lack of space caused by of pet overpopulation, only six cats were available for adoption. The rest of the cages were empty.

At a traditional animal shelter, you will find animals being killed despite offers from other non-profits and rescue groups to save those very animals. In fact, 71% of New York rescue groups and 63% of Florida rescue groups reported shelters killing the very animals they had offered to save. And both HSUS and the ASPCA believe this is as it should be as both have fought to defeat legislation which would have made it illegal for shelters to kill animals who qualified rescue groups are willing to save—legislation that has already saved hundreds of thousands of lives in other states. Since California passed such a law over the opposition of HSUS, the number of animals transferred to rescue groups rather than killed went from 12,526 to 58,939-a 370% increase because shelters were now required to work with rescue groups.

Animals in shelters are also killed because the shelter director refuses to implement a comprehensive foster care program for neonatal puppies and kittens, choosing to kill those animals instead. At one such shelter, the director fired staff and volunteers who were bottle feeding orphaned baby animals on their own time and at their own expense. And at traditional shelters animals are killed because shelter directors do not want to make the effort to implement all the other alternatives that already exist (programs and services collectively known as the No Kill Equation): neuter and release, offsite adoptions, pet retention and field service programs to reduce impounds, as well as medical and behavior rehabilitation programs, to name just a few.

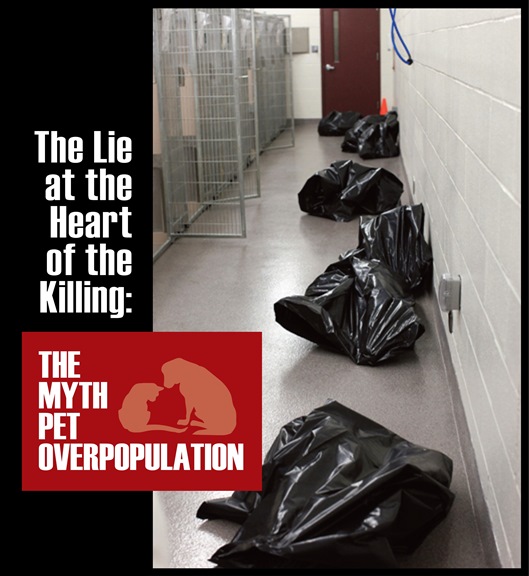

In the end, killing is occurring in our nation’s shelters not because there are too many animals, but because killing is easier than doing what is necessary to stop it, and because as heartless as that reason is, shelter directors have been allowed to do it anyway. Why? Because the people who should be their fiercest critics—those within the animal protection movement itself—have provided them political cover by falsely portraying the killing that they do as a necessity born of pet overpopulation. In fact, the lie of pet overpopulation is at the heart of the killing paradigm. It is the primary excuse that allows shelter directors to shift the blame from their own failure to save lives to someone else. And it is the excuse that has, for decades, kept the animal protection movement wringing its hands, spinning in endless, hopeless circles, trying to “solve” the problem of shelter killing by attacking a phantom cause, rather than the one that is truly to blame.

There are now No Kill communities across the U.S. and abroad: in New York and in California, in Colorado and Virginia, in Utah, Indiana, Michigan and Kentucky, in Nevada, and across the globe, including areas suffering from high rates of unemployment and foreclosure. Washoe County, Nevada, for example, has been very hard hit by the economic downturn. Loss of jobs and loss of homes are at all-time highs. In fact, the state of Nevada has one of the highest unemployment rates in the nation. As a result, the two major shelters (Washoe County Regional Animal Services and the Nevada Humane Society) together take in four times the per capita rate of Los Angeles, five times the rate of San Francisco, 10 times the rate of New York City, and over two times the national average. If there was ever a community which, according to conventional wisdom, could not adopt its way out of killing, it is Washoe County. But they are doing just that. And it didn’t take them five years to do it. All these communities did it virtually overnight, by implementing proven strategies to lower impounds and relinquishments, increase redemptions, return animals to their responsible caretakers and free living cats to their habitats, while adopting out the remainder.

From both the perspective of animals and the perspective of the true animal lover, the fact that pet overpopulation turns out not to exist can only be described as welcome news. That the main excuse historically used to justify the need to systematically poison or gas to death millions of dogs and cats turns out to be a fabrication should be cause for celebration. One would expect that the leadership of the animal protection movement and those within the grassroots who defer to them would not just embrace this news but would shout it from the rooftops. Tragically, that has not been the case. Rather than accept and then evolve their approach to this issue in light of new information (a study conducted by HSUS itself proved that demand for animals vastly exceeds the number of animals being killed in shelters), they have instead tenaciously clung to and even jealously guarded the idea of pet overpopulation, working to stall its rapidly diminishing sway over animal lovers by repackaging pet overpopulation with “new and improved” labels such as “Regional Pet Overpopulation, “Shelter Overpopulation” or reasserting the efficacy of pet overpopulation by redefining the terms of the debate in a specious manner.

REGIONAL PET OVERPOPULATION: SAME ARGUMENT, SAME INESCAPABLE CONCLUSION

According to these groups, while pet overpopulation might not exist nationally, it does exist regionally in areas with higher rates of poverty, particularly the South. Yet the rationale for this argument is as convoluted as that for the one they now have been left with no choice but to admit is insupportable. Not only does it ignore the experience of economically distressed areas like Washoe County; it ignores the fact that each of the communities that have succeeded were also once steeped in killing, claiming at one time they had no choice but to kill by using the same excuses that have been proven false by virtue of their own success (almost always after a regressive shelter director was replaced with a progressive one). It ignores the growing number of communities with save rates between 90% and 99% in the South. And it ignores that while each of our nation’s successful communities are demographically and geographically diverse, the one thing they do share is that their success was neither a fluke nor the result of a very specific set of circumstances which set them apart from other American communities. Each of those shelters is succeeding for one reason and one reason alone: the shelter itself changed the way it operated, rejecting killing in favor of existing alternatives and by rejecting the false premise that they can’t save them all because of pet overpopulation.

In the end, the regional pet overpopulation argument has the same flaws as the traditional pet overpopulation problem which its proponents increasingly, though grudgingly, admit does not exist. With no statistical analysis to support it and the experience of communities with extremely high per capita intake rates proving that No Kill can succeed in spite of such challenges (today there are No Kill communities with per capita intake rates 20 times higher than New York City, the most densely populated city in America), regional pet overpopulation is the same argument with a new label and every bit as devoid of verifiable, concrete data to back it up.

Let’s look at it another way. There are roughly 165 million animals in people’s homes and the numbers are not just holding; they are growing. If shelters increase the number of animals who come from shelters by a few percentage points, we would be a No Kill nation today. A two percent increase would replace all killing with adoption. And because some of that would be replacement “markets” (a pet dies or runs away) and not just new “markets” (someone doesn’t have a pet but decides to get one or has one and decides to get another), what statisticians call a combination of “stock” and “flow,” it is actually less. Take a state like Michigan, where some claim that regional pet overpopulation exists because of economic distress and high rates of unemployment. Today, roughly 85,000 animals statewide are losing their lives annually. Of those, just over 80,000 animals are healthy and treatable. Of those, at least another 4,000 can and should be reunited with their families (on average, Michigan shelters have 10% reclaim rates, a figure that is not only far below the national average, and a fraction of the most successful communities in the nation, but a statistic that could be dramatically improved if the reclaim protocols of the No Kill Equation were followed). If “feral” cats were neutered and released rather than killed as the No Kill Equation also mandates, then under a worst-case scenario, about 70,000 additional homes need to be found for Michigan to become a No Kill state. That amounts to just over ½ of one percent of Michigan’s 10,000,000 residents. Even if one is looking at the number of households instead of the number of people, it’s less than two percent. How is that evidence of a “regional pet overpopulation” problem? It isn’t. In fact, the evidence reveals that the opposite is actually true, which is the case in communities nationwide, too.

SHELTER OVERPOPULATION: IT’S DAJA VU ALL OVER AGAIN

One proponent of the pet overpopulation argument has gone so far as to admit there is neither national pet overpopulation, nor regional pet overpopulation, but instead claims we have “shelter overpopulation.” Under this argument, if a shelter has 100 cages, when the 101st animal comes in, there is “shelter overpopulation” which makes killing the 101st animal justified. To begin with, the argument lacks any threshold or standards to ensure protections for animals of any kind. Indeed, by this logic, there is no killing that cannot be justified. If this same community dismantled 95 of the 100 cages, they would be morally justified in killing the 6th animal who came in. Moreover, it does not take into account foster homes, temporary cages and kennels, doubling up animals, pet retention programs and adoption campaigns—all the alternatives to killing that successful communities use to replace killing when cages get full. It presupposes that No Kill communities never have more animals than cage space when it is a given that, at some point, every shelter will face such a scenario, especially during peak intake times such as spring and summer.

The argument also ignores the fact that a shelter can always add more cages to accommodate population. As director of the shelter in Tompkins County, New York, I converted the garage, which housed two vans, into two rooms: an overflow infirmary and a nursery for kittens. Prior to my arrival, our vans, tools to help us in our mission, enjoyed protection from the elements while sick animals and kittens, who were our mission, were being killed for “lack of space.”

There was nothing preventing my predecessor from doing what I did. But by the “shelter overpopulation” argument, his killing of kittens rather than sending them into foster care or adding more cage space was entirely justified. Is that really the standard of care we want our nation’s shelters to follow—in essence, no standards at all? Anything goes if the alternative to killing is having to embrace an alternative to killing? In the end, the proponents of “shelter overpopulation” have simply taken the excuses used to justify killing on a macro-scale and reduced it to the micro. But it is the exact same argument, flawed for the same reasons and equally as unethical.

MAKING THE NUMBERS FIT THE CONCLUSION

In the face of this irrefutable evidence, some apologists—mostly supporters of PETA’s campaign of dog and cat extermination (killing as they do roughly 97% of all the animals they seek out)—have started to cook the books. No longer able to rationalize a supply and demand imbalance given both the data and experience of successful communities, they are packing the numbers on the supply side to make their case appear more plausible. While tacitly admitting that the data and experience do not lend themselves to the notion of a supply-demand imbalance and thus, a “need” to kill animals (itself a logical and unethical fallacy even if true as will be discussed below), they argue that when calculating the number of animals in need of homes nationally, we must include all the animals living on the street as well, not just the ones being killed in shelters. When you include all the animals living on the street, they argue, pet overpopulation is real.

There are many flaws inherent in this argument as well, the first being that it introduces into the equation a whole category of animals who, while their well-being is important, are not relevant to the very specific discussion of shelter killing for the simple fact that they are not in shelters. In other words, while adding the number of animals in shelters combined with the number of animals living on the street would provide a statistic of how many animals in America might not have a human address, that number would not reflect how many animals are under an immediate death threat at their local shelter which is, after all, the killing pet overpopulation has always been used to justify. Nor does the existence of such animals impact the demand side of the equation which, as already explained, so vastly exceeds the supply of animals in shelters that it can even accommodate homes lost to commercially-sourced animals such as those from breeders and pet stores, as well as those adopted from the streets. In short, while expanding the supply side of the pet overpopulation argument in this way is an attempt to obscure and confuse the issue, it does not change the conclusion supported by both fact and experience: every year, there are more homes available than there are animals being killed in shelters.

Nor does the implied corollary to their argument stand up, either. Are those who make this argument implying that all free-living animals should be brought into shelters and therefore, if they were, pet overpopulation would in fact exist? That, after all, is the inference of their argument. First and most significantly, arguing that pet overpopulation would be real if all free-living animals were admitted to shelters is to introduce a hypothetical and irrelevant scenario into a discussion about a very real problem. For four million animals every year, shelter killing is a grave and immediate danger. To argue for the existence of the disproven but primary excuse used to justify that killing based not on what is happening but what might happen were all free-living animals to be admitted into shelters reduces a serious and weighty discussion to the realm of make believe.

A genuine commitment to animal welfare requires an honest assessment of reality and the genuine threats which animals entering shelters face. Admitting extraneous, unrelated issues into the discussion is an attempt not to illuminate, but to obscure. And analyzing the validity of historical claims used to justify the systematic killing of millions of animals should not be a sophomoric exercise in rhetoric or debate, but a serious discussion that seeks to inform and influence our positions and actions on behalf of animals in a responsible, thoughtful and fact-based way.

Moreover, those who advocate for animals should oppose any suggestion that animals on the streets would be better off in those places that present the greatest threat to their lives: the local animal shelter. Nor would loss of life, though the greatest harm, be the only one such animals would likely face if admitted to shelters. Although the animal protection movement has perpetuated the fiction that our nation’s shelters provide a humane and compassionate safety net of care for our nation’s homeless animals, the facts tell a very different, very tragic, story. In truth, the first time many companion animals experience neglect or abuse is when they enter a shelter.

As the movement to end shelter killing has grown in size and sophistication, the networking made possible through the internet and social media has allowed animal lovers to connect the dots between individual cases of animal cruelty and neglect in shelters nationwide. These incidents reveal a distinct pattern. Animal abuse at local shelters is not an isolated anomaly caused by “a few bad apples.” The stunning number and severity of these cases nationwide lead to one disturbing and inescapable conclusion: our shelters are in crisis. Frequently overseen by ineffective and incompetent directors who fail to hold their staff accountable to the most basic standards of humane care, animal shelters in this country are not the safe havens they should and can be. Instead, they are often poorly managed houses of horror, places where animals are denied basic medical care, food, water, socialization and are then killed, sometimes cruelly.

Until we reform our shelters, the last place an animal advocate should wish an animal to end up, including those animals who live on the streets, is the local shelter. Not only is life on the street safer than a stay in an animal shelter, but the very thing animal shelters are supposed to provide to homeless and stray animals—reunion with their home or adoption into a new one—are more likely to happen to an animal on the street than one entering a shelter. The likelihood of an animal being reunited with their human caretakers is greater for cats, for example, if they are allowed to remain where they are rather than being impounded. In one study, cats were 13 times more likely to be returned home by non-shelter means (such as returning home on their own) than through the pound. While another study found that people are up to three times more likely to adopt cats as neighborhood strays than from a shelter.

Nor is life outside a human home the tragedy it is so often painted to be by shelter killing apologists seeking to justify killing by falsely portraying the alternative as even worse. The risk of an untimely death for street cats is extremely low, with outdoor cats living roughly the same lifespan as indoor pet cats. In a study of over 100,000 free-living cats, less than one percent of those cats were suffering from debilitating conditions. In other words, the risk of death is lower and the chance of adoption higher for cats on the street than cats in the shelter. And in countries outside the U.S., neuter and release of dogs is not uncommon and regarded, as it should be, as an infinitely better alternative than impound and potential death.

Like pet overpopulation, the argument that animals are better off dead than living on the street flies in the face of actual evidence. And just as significant, it also flies in the face of our common experience as living beings who, if given the choice between death at a shelter and survival by our wit, instinct and the chance of benefiting from the kindness of strangers, would choose the latter without a moment’s hesitation. Not only would this choice be our natural impulse, the facts show it would be the smart one, too.

With shelter killing being the leading cause of death for healthy animals in America (and therefore the cause of the greatest possible harm to befall homeless animals), the No Kill movement is focused on bringing this very specific harm to an end. We do not need to keep killing shelter animals because there are other animals living on the street. That is a non sequitur that groups like PETA conveniently ignore when they perpetuate this false choice and fallacy in order to justify the killing of those they theoretically exist to protect.*

But even if we ignored the illogic, their argument also falls apart in the absence of any concrete data to support their case that when the number of animals living on the streets is factored into the supply side, pet overpopulation exists. No one knows for sure the number of animals living on the street. If those who continue to claim pet overpopulation is real because the number of animals exceeds demand for animals and that this supply-demand imbalance requires shelters to kill animals, the burden is on them to prove it: what is the supply side of the equation? When you are preaching death, when you are promoting death, when you are excusing death, and when—in the case of PETA and its supporters—you are paying for and actually doing the killing, the burden to prove its “necessity” is on you.** In short, one better know the supply side of the equation before using use an argument dependent upon it to justify a mass slaughter, and, predictably, just as is true with the traditional notion of pet overpopulation which they have perpetuated for decades, they do not.

Moreover, the best estimate (and it is still largely a guess) is that about 12 million cats and far fewer dogs are living on U.S. streets, parks, and alleyways. Of course, feral cats and in some inner cities feral dogs, make up some percentage of those animals and they are not homeless. The outdoors is their home and the same is true of friendly community cats, too: those cats who are not “feral” because they are tame, but are nonetheless cared for by a person or as is often the case several people, but—as recent studies from the veterinary community confirm—are in no way suffering because of it, as proponents of round up and kill campaigns like PETA and its adherents falsely claim.*** Nonetheless, when you remove “feral” cats and dogs from the total numbers, we’re still dealing with a figure that is less than total demand, so the math still does not hold up. Even so, as noted above, it is irrelevant. For those who do actually enter shelters—an estimated three million animals a year who are dying but for a home—there are plenty of homes available if, instead of killing them out of convenience, shelters better promoted the animals and then actually kept them alive long enough to find homes through comprehensive adoption campaigns.

ACCEPTED ON FAITH

So given that there is so much information and experience working against the notion of pet overpopulation and given that to believe in pet overpopulation is to condone the excuse that allows for the killing of four million animals every year, why do people who claim to be animal lovers not only to cling to it, but work so hard to maintain it or to try to revive its fading supremacy through rebranding? There are three primary reasons.

First, until very recently, pet overpopulation was an unquestioned gospel within the animal protection movement. Repeated ad infinitum within the animal protection community as means of explaining shelter killing and distinguishing it from other forms of killing by virtue of its “necessity,” (especially since this form of killing was being done by those who claimed to be a part of the animal protection movement itself) its prevalence and undisputed authority for so many decades gave it the appearance of truth rather than what it was all along: a mere hypothesis, and one that, when subjected to scrutiny and weighed against the evidence, collapses like a house of cards. Nonetheless, the universal acceptance of pet overpopulation that dominated the animal protection movement at one time-a groupthink mentality that accepted it as an a priori truth outside the bounds of investigation or analysis—meant that to ultimately question its precepts was regarded as heresy, opening up those who exposed its fallacies to condemnation, scorn and allegations of fraud.

The motives of those who seek to expose the lie at the heart of the killing, the myth of pet overpopulation, have been maligned and misrepresented, creating a climate of suspicion within the animal protection movement not only about those who question the doctrine, but the very act of questioning it at all. Why? Because if pet overpopulation is a myth, then the killing being done in shelters is immoral, and those who do that killing—friends and colleagues within the animal protection community itself—are behaving unethically and irresponsibly towards animals, a troubling and deeply unsettling conclusion that for many people within the animal protection community is better left unreached. Sadly, for many people who know and support organizations and individuals doing the killing or which provide it political cover, such allegiance is more important than the lives of the animals they are supposed to represent. To them, pet overpopulation, the historical narrative which has shielded those people from accountability, must not be exposed as a lie, and anyone who tries to do so is the enemy.****

SPAY/NEUTER: A FALSE IDOL

The second—and probably more ubiquitous—reason that some animal activists are resistant to the idea that pet overpopulation is a myth is because they irrationally fear that if the public finds out the truth, the public will no longer spay/neuter their animals, which they continue to view as critically important. Why do they believe sterilization is so critically important? Because, like the pet overpopulation, they have been told over and over again, and for years on end, that it is.

In fact, spay/neuter has been the cornerstone of companion animal advocacy for decades. Why? Because it does not threaten those running shelters. Whereas the other programs of the No Kill Equation such as foster care, comprehensive adoption programs and proactive redemptions which are vitally important—even more essential—to saving lives than spay/neuter place the responsibility for lifesaving on the shelter; spay and neuter places the responsibility on the public. And, therefore, unlike those other programs, spay and neuter has been and continues to be the one program of the No Kill Equation to which every shelter director and every large national group pays homage. And that is also why so many animal activists argue, as they have they have been schooled to do and despite no evidence to prove it, that spay and neuter alone is the key to ending the killing. But is it true? In fact, it is not.

Yes, spay and neuter is important. It is program of the No Kill Equation and I, along with other No Kill advocates, promote it. Because even though pet overpopulation is a myth, continued promotion and availability of high-volume, low-cost spay/neuter is a means to reach stasis in shelters where adoptions equal intakes, making the achievement of a No Kill nation even easier to achieve. This is important because the lower the intake, the easier it is for even unmotivated, ineffective and uncaring directors (in short, your average kill shelter director) to run a No Kill shelter. In other words, we want to eliminate those communities with high intake rates (like Washoe County) needing thoroughly committed and hardworking leadership to stop killing. Moreover, if spay/neuter allows a community to drop intakes significantly enough that they are unable to meet adoption demand, they can begin importing animals from high-kill rate jurisdictions and save those lives, too. Until all communities are No Kill communities, this is a very good thing to have happen.

But despite the role spay and neuter plays in helping a community more easily achieve and sustain No Kill, the fact remains that despite the privileged position spay/neuter has historically enjoyed within the animal protection movement, it alone has never—never—created a single No Kill community. In fact, communities with very high per capita intake rates have achieved No Kill without a comprehensive public spay/neuter program. We cannot neuter our way out of killing and no U.S. community ever has. That honor belongs to the No Kill Equation as a whole, a series of programs and services which require a shelter to harness a community’s compassion and which therefore also prove that in order to succeed, a shelter must embrace rather than alienate the people it serves.

The No Kill philosophy recognizes that far from being the cause of shelter killing, the community is the key to ending it. It recognizes that while some people are irresponsible, most people are trustworthy and will do right by companion animals if we explain how they can do so. To the extent that spay and neuter is one of the programs that helps a shelter more easily achieve No Kill, that positive outcome is enough to encourage most people to do right not just by the animals, but by the shelter which shares their values and which they want to support and enable in its success. We need not fear monger with pet overpopulation and by extension, the threat that we will kill animals—or even actually kill animals—to get people to do the right thing. When we make it easy for them to do so—such as making spay/neuter affordable—they will. And studies and experience prove it.

Finally, believing that spay/neuter alone holds the key to ending the killing fails to recognize the most essential and tragic truth about animal sheltering in America today: we already have alternatives to killing, alternatives that the vast majority of shelter directors simply refuse to implement. And how can you save animals in a shelter run by a director who simply refuses to stop killing? Moreover, lamenting that we would be finally able to end the killing if only everyone sterilized their animals or could be forced to do so is like wishing that a historically popular but ineffective remedy for a particular disease would work when a cure has already been found. Not only does such an attitude perpetuate ignorance and helplessness by failing to acknowledge a genuine solution that already exists, but it siphons energy that should be directed towards implementing the real remedy into mourning the failure of a hopeless one. How does that help animals?

It doesn’t. Indeed, the notion that we must continue to promote the myth of pet overpopulation—which condones and enables killing—in order to encourage people to spay and neuter—which has only ever been important because it is a means to prevent killing—is an inversion of priorities. It is to encourage the disease and forsake the cure, in favor of the medicine.

Every animal lover has a responsibility to recognize that we don’t need to figure out how to end the killing anymore. It is no longer a mystery—the No Kill Equation provides the answer. Our job now is to make sure the roadmap we already have is implemented in every shelter in America.

PET OVERPOPULATION AS POLITICAL COVER

The third and final reason that people cling to the myth of pet overpopulation is because they have a vested interested in killing. This includes directors who run poorly performing shelters. It includes government bureaucrats in these communities who are supposed to oversee these shelter directors but refuse to hold them accountable. It includes national organizations like the Humane Society of the United States, the ASPCA and PETA whose companion animal divisions are staffed with former shelter directors and employees who themselves failed to save lives when they worked in shelters and are therefore not only threatened by No Kill success, but are committed to shielding their friends and colleagues still working in shelters from greater accountability. It includes the supporters of those groups whose identity is so wrapped up in that support that they not only reject any criticism of the groups no matter what the evidence, but take such criticisms as a personal affront, thus willfully enabling killing through an unhealthy, codependent relationship that puts their own narrow self-interest before the lives and well-being of animals. And lastly, it includes the heads of organizations who claim to support No Kill, even claim to be striving toward No Kill, but who rely on the myth of pet overpopulation to justify their five and ten year No Kill plans in light of communities which have achieved it virtually overnight.

For such groups, pet overpopulation is a tool used to distinguish their community from those that are already successful, a means of obscuring the truth by portraying their community as more challenging than those that have already succeeded, even though, in truth, the thing that sets successful communities apart from theirs is a greater commitment to implement alternatives to killing and a greater determination to overcome the resistance of those who stood in the way.

A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT

But let’s ignore all the reasons why pet overpopulation is in fact a myth and all the reasons why people who claim to love animals so vehemently defend it. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that “pet overpopulation” is real. Does that change the ethical calculus? It does not. Shelter killing would still be immoral. Advancing a practical over an ethical argument has long been the safe haven for those who want to justify untoward practices. Even accepting the sincerity of the claim, even if the practical calculus was correct, protecting life that is not suffering is a timeless and absolute principle upon which responsible advocates must tailor their practices.

Indeed, the underpinning of the No Kill movement is that it goes beyond what is commonly assumed to be a practical necessity. It is, first and foremost, a movement of beliefs, of morality and ethics, of what our vision of compassion is now and for the future. Its success is a result of the philosophy dictating our actions and thereby prompting us to do better; to embrace more progressive, life-affirming methods of sheltering. Before many of us within the No Kill movement felt comfortable with the answer to questions of whether or not “feral” cats suffered on the street and whether or not No Kill was possible, we had already rejected mass killing. We had rejected practical explanations based on a “too many animals, not enough homes” calculus, or that a humane death was preferable to potential future suffering. Even though early in the No Kill movement’s history, though the practical alternative of the No Kill Equation was yet unknown, the movement still recognized that whatever practical explanations there were to “justify” it, the killing was still wrong and must be rejected.*****

No Kill is, at its core, about the rights of, and responsibilities we have to individual animals. This tenet is summarized by one of the Guiding Principles of the U.S. No Kill Declaration:

Every animal in a shelter receives individual consideration, regardless of how many animals a shelter takes in, or whether such animals are healthy, underaged, elderly, sick, injured, traumatized, or feral.

More often, however, the practical calculus is wrong and at least historically, has been used to excuse atrocities. Ethics will always trump the practical and the two are seldom so inexorably linked that an untoward action must follow some fixed practical imperative. Every action taken by animal advocates must be subservient to preserving life, a principle that not only puts our movement in line and on par with the successful rights-based movements that have come before ours, but is a philosophy that fosters the motivation necessary for us to figure out how we can bring our aspirations into reality. That is the job and duty of the animal protection movement, not—as it has historically done—justifying or enabling the killing of animals.

THE CONCLUSION

We can end the killing and we can do it today. And in roughly 300 cities and towns across America, we’ve done exactly that. That is the good news that comes from the understanding that “pet overpopulation” doesn’t exist. It means the killing is not a “necessary” evil. It is, quite simply, evil. It means animals don’t have to die as we have been told for so long.

If you truly love animals, if you are a person who claims to be their advocate, you do not respond to that news with indignation, scorn, anger, apoplexy, by shooting the messenger or by attempting to obscure the issue for others with irrelevant and unrelated tangents. You celebrate, and then you share that good news with everyone you know who loves animals, too, so that the pernicious and persistent myth at the heart of the killing—the lie that is responsible for violent atrocities against millions of animals every year—will finally die. Anything else is unethical. It is enabling shelter killing. And it is turning a blind eye to a solution that will spare millions of animals from losing the one thing that is, as is true for each of us, more precious to them than anything else: their lives.

——

* They also ignore the fact that PETA believes those animals should be killed, too, even if they are not suffering. In the last 11 years, PETA has killed 29,426 animals, including those they themselves have called “healthy,” “adoptable,” “adorable,” and “perfect” and even after promising that they would find the animals a home. They do not have adoption hours, they do not have an adoption floor, they do not market their animals, and most are killed within 24 hours. They have called for the automatic killing of all dogs who look like “pit bulls” in shelters. They have called for the round up and killing of even healthy feral cats. They have defended poorly performing and even violently abusive shelters. And they fight shelter reform legislation to mandate the common sense programs of the No Kill Equation, such as TNR and rescue rights. Whatever methods PETA uses to justify shelter killing should be approached with the understanding that PETA is motivated by a very different set of priorities than the vast majority of people, and a set of priorities that are in fact the opposite of that which is generally ascribed to them given their name and reputation. Although they try to obscure their true agenda by working to convince their supporters and animal lovers that they believe killing is a regrettable necessity, in truth, their more candid statements and most significantly, their actions, reveal that those who work at PETA believe that life is suffering, the living want to die and killing them is, as Ingrid Newkirk herself stated, a “gift.”

** Although, in truth and from an animal rights perspective, there is no information or practical argument in defense of shelter killing that supersedes every animals’ inherent rights, chief among them the right to live.

*** It is never ethical to kill an individual animal based on a group dynamic. Even if it could be proven that most free-living cats die prematurely due to disease or injury (which is by no means true, but postulated for the sake of argument), it would still be unethical to kill any individual cat because not only do that cat’s inherent rights ethically prohibit it, but there is no way to know if that particular cat will ever succumb to such a fate, let alone when. In fact, even if it was known that a particular cat would get hit by a car two years from now, it isn’t ethical to rob him of those two years by killing him now. Furthermore, those are not the facts; free-living cats are not disproportionately suffering. In fact, the largest study of “feral” cats conducted in the U.S. showed baselines of health and longevity almost identical to pet cats.

**** Because of my efforts to expose the lie of pet overpopulation, I have been maligned and repeatedly misrepresented in a variety of ways. Rumors about me abound, stating that I do not represent the animals, but industries that harm them. One of the most pervasive lies about me is that I am a front for puppy mills—an entirely baseless accusation intended to scare animal lovers away from listening to what I have to say. Puppy mills cause horrible animal suffering and death—two things I have committed my life to opposing. I support laws banning the sale of purposely bred animals from pet stores. I’ve written articles and held workshops on closing down puppy mills. I do not get money from groups that oppose the rights of animals. And regardless of why animals are being killed, they are being killed, and as long as they are, I believe that it is incumbent on everyone seeking to bring an animal into their life to either rescue or adopt from a shelter. In short, adoption and rescue are ethical imperatives.

***** Indeed, the very fact that the myth of pet overpopulation to rationalize the killing and the euphemisms used to describe it such as “euthaniasia,” putting them to sleep,” and “humane death” came into existence are proof that even those doing the killing understood that it was so perverse it needed masking, an artifice to shield its ugly reality from the public.

About the data: When I wrote Redemption in 2007, I was very conservative. HSUS’ own numbers prove that the number of people who will bring a new animal into their home far exceeds the number being killed in shelters but for a home. And HSUS is not alone. The data for this analysis came from a number of sources, including national surveys done by Maddie’s Fund, HSUS, Mintel, and Petsmart Charities. It includes data from shelters that have statewide reporting such as Virginia, Michigan, North Carolina and California, among others, and a database of about 1,100 organizations, almost one-third of the U.S. shelter total.

For further reading:

Can You Neuter Your Way Out of Killing?

—————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.