We’ve made tremendous progress as a movement, but not only is there still a long way to go, some communities are moving in the wrong direction.

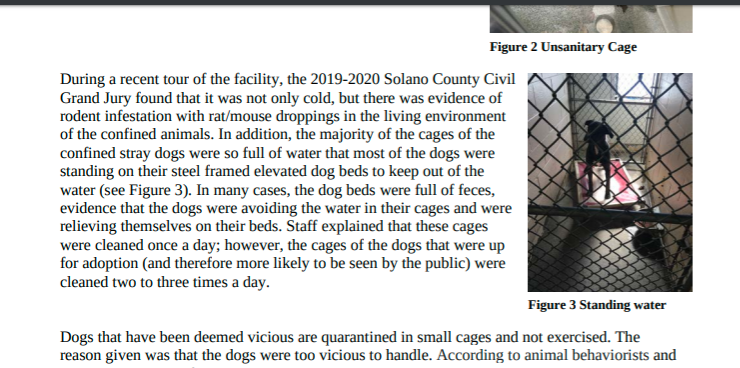

The Solano County Grand Jury recently issued a report recently after doing an inspection of the county shelter. Jurors found “evidence of rodent infestation with rat/mouse droppings in the living environment of the confined animals. In addition, the majority of the cages of the confined stray dogs were so full of water that most of the dogs were standing on their steel framed elevated dog beds to keep out of the water: In many cases, the dog beds were full of feces, evidence that the dogs were avoiding the water in their cages and were relieving themselves on their beds.”

In addition to failing to keep up with the hygienic needs of the animals by staff, the Grand Jury found that elected officials have neglected both the staffing needs of the shelter by cutting back staff when they should have been adding them, as well as maintaining an outdated facility. It noted that as early as 2006 and repeatedly thereafter, they expressed alarm at the condition of the physical shelter, calling “construction of a new shelter a ‘high priority.'”

According to a local news report, “The required response from the Sheriff’s Office had not yet been filed with the grand jury” and “A call seeking comment from the Sheriff’s Office was not returned.” But one staff member, who was not identified, said they are overworked, understaffed, the shelter is located near a field which invites rodents, and as for the the dog beds being “full of feces,” “Everybody poops!” and little dogs don’t do it “where they are supposed to.”

There is little question that the No Kill movement has achieved unparalleled success. In the 1970s, some 17 million animals were killed in pounds annually. Today, about 1.5 million are killed. That’s roughly a 90% drop in killing, despite a doubling of the number of animal companions. Its been referred to as “the single biggest success of the modern animal protection movement.” And even Solano County has seen significant increases in its placement rate, more than doubling since 2010. All of that is worth celebrating. But clearly, there is still a long way to go.

And unfortunately, the pandemic has exposed some alarming deficiencies. While many communities are rising to the challenge by embracing ingenuity, a “can do” attitude, and technology to save the animals, and, as a result, “have placed record numbers of dogs, cats and other animals” and are finding themselves empty for the first time in their history; others have turned their backs on animals by closing their doors, telling people who find stray dogs to turn them loose, telling those who find stray kittens to leave them in the street, and by mass killing.

Volunteers in Broward County, FL, for example, claim that the pound killed hundreds of dogs and cats in March and April, including those with rescue commitments and those where rescue groups were never notified despite a mandate (at the very least, an ethical mandate) to do so from a Commissioner. Moreover, they write, “The continued closure gives dogs and cats even less of a chance of adoption than usual. On Saturday, many potential adopters were turned away, the gates firmly locked.”

And even more alarming, some shelter officials have floated making some of those practices permanent. An April memo written by the Chief at Austin Animal Center proposed a future vision of “not accepting strays at the shelter” even after the pandemic is over as a way to limit intakes. According to a local news report, “Those plans include turning away strays, and only taking in sick and injured animals and those with serious behavioral problems.” While that proposal is “outdated” and no longer reflects current thinking, say shelter managers, a local news report noted that, “The Austin Animal Center is accepting very few healthy stray animals right now and Austinites are being encouraged to leave the animals on the street in the hope they’ll wander home, or take them in themselves.”

Working harder to get strays home and working to rehome animals without their having to come into the shelter is certainly worth doing and doing better. I argued that in an essay ‘It Takes a Village’ back in the late 1990s, so it is hardly a revolutionary concept. Indeed, some communities have been doing it for decades. In one community I worked with, roughly 6,000 wayward animals were returned home instead of being brought to the shelter. And while it is also true that healthy cats who are not lost are sometimes taken to the shelter by well-meaning people where they become lost in the process, clearly, some directors are taking the concept of “community sheltering” to mean turning their backs on animals in need.

To them “community sheltering” is a euphemism for no sheltering, putting the onus on others to do the job they are paid to do. To me, the future of animal sheltering is the exact opposite: having the local shelter play a more central role for all of a community’s animals. What that vision looks like is an article for another day:

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.